With last week’s reading we have completed more than half of The Crucifixion. The book has 612 total pages, so when we finished reading page 306, we passed the halfway mark.

Whoa oh, we’re halfway there, whoa oh, livin’ on a prayer!

Seriously though, it feels good to be halfway through our reading journey. When I’m running a long race (like a half or full marathon) or when I’m hiking a long trail, I feel a little burst of energy at the halfway point. It’s all downhill from here!

So we finished up Rutledge’s chapter on “The Blood Sacrifice” as one of the biblical motifs for understanding atonement. This metaphor for atonement helps us to see the truth that sin costs something (245). The blood of Jesus is the cost God “paid” for our liberation from sin. According to Rutldege, “One of the simplest ways of understanding the death of Jesus is to say that when we look at the cross, we see what it cost God to secure our release from sin” (246).

The death of Jesus was not God’s Plan B. Rather Jesus died for our sins according to the the Scriptures, the Hebrew Scriptures, the Spirit-inspired story of Israel. Moreover Jesus sacrificial death flowed from who God is.

The book of Hebrews becomes an invaluable resource for understanding blood sacrifice from a Jewish perspective. Hebrews is deeply pastoral. Hebrews wants God’s people to see not only the cohesion between the mission of Israel and the death of Jesus, but Hebrews also wants God’s people to take comfort and courage in what God and done in and through Jesus. “He has appeared once for all,” writes the writer of Hebrews, “at the end of the age to put away sin by the sacrifice of himself” (Hebrews 9:26).

The blood sacrifice motif can be seen in the sacrificial lamb in Isaiah 53:7 and the Passover Lamb of the Exodus. “Christ, our paschal lamb, has been sacrificed for us” (1 Corinthians 5:7). While there is an image of a militant lamb in Jewish apocalyptic literature popular in the day of Jesus, the New Testament writers, particularly John the Apostle and John the Revelator, depict Jesus as the Lamb of God who reigns not by slaying his enemies, but by being slain.

[Side note: I really wish I had read this book a year ago, because I would have incorporated some of this material on the Lamb of God into my new book Centering Jesus: How the Lamb Transforms our Communities, Ethics, and Spiritual Lives. The book releases August 22!]

We also see the sacrificial Lamb in the story of Abraham and Isaac on Mt. Moriah. Rutledge argues (as I argue in Centering Jesus) that Jesus can be identified not with Isaac but with the lamb/ram that God provided for Abraham. Abraham as a father would not be sacrificing his son, because this is not what God is like. A substitutional sacrifice was offered in place of Isaac. The Father doesn’t sacrifice his son; the Father provides the sacrifice for his son!

Rejecting Propitiation

In this chapter on blood sacrifice, Rutledge dives into the age-old debate on the proper meaning the Greek word hilasterion, used in numerous places through the New Testament, but most notably in Romans: “...whom God put forward as a sacrifice of atonement [hilasterion] by his blood, effective through faith…” (Romans 3:25 NRSV).

The KJV translates this Greek word using the very technical English word “propitiation,” meaning a sacrifice offered to appease an angry deity “aimed at satisfying the divine wrath” (279).

Many biblical interpreters, myself included, prefer the interpretation of hilasterion as expiation and not propitiation. Expiation is the removal of sin. Rutledge points out that with expiation that barrier between God and humanity is within humanity, our sin is the barrier. With propitiation the barrier between God and humanity is within God, thus “the insistence on propitiation has, perhaps unwittingly but nevertheless wrongly, divided the Father from the Son” (279). She is right. Not only does propitiation have exegetical problems that she does not mention here, but propitiation has serious theological flaws.

The exegetical problem she doesn’t mention is in the Old Testament use of hilasterion. It is the Greek word used in the LXX to refer to the mercy seat, the lid of the Ark of the Covenant where blood was sprinkled on the day of Atonement. The result of the sprinkling of blood on the hilasterion was not the satisfaction of God’s righteous anger, but according to Leviticus 16:16, 19, & 30, it was to remove the stain of sin from Israel. Rutldege doesn’t mention this but N.T. Wright describes it in The Day the Revolution Began and I reflect on it in N.T. Wright and the Revolutionary Cross.

The theological problem with propitiation is the division it creates within the Trinity. For these reasons, “any concept of hilasterion in the sense of placating, appeasing, deflecting the anger of, or satisfying the wrath of, is inadmissible” (280). She has much more to say about God not being divided against God’s own self. Sin was judged and condemned in the death of Jesus, but Jesus himself was not condemned. The Son doesn’t change the Father’s disposition towards us.

Reclaiming Redemption

The next motif to explore is that of ransom and redemption. It informs the language of Jesus “paying the price for our sins” which is popular in evangelical circles. Paul writes, “You were bought with a price” (1 Corinthians 6:19-20, 7:23). Jesus himself said he came to give his live as “a ransom for many” (Mark 10:45). While these metaphors allude to Jesus’ sacrificial death they are not used by Paul or Mark in the context of a longer theological argument regarding atonement. Nevertheless they do indicate the cost, the price, and the value of Jesus’ death.

What Rutledge emphasizes in the ransom metaphor is “Jesus himself is the price of our redemption” (289). She is helpful here. It is not only the blood of Jesus that is the price but his entire life. In other words, it is not only his death but his incarnation, ministry, life, death, resurrection, and ascension that is salvific.

Rutledge again draws on Trinitarian theology to note that the entire Trinity is at work “buying back” humanity from the unholy trinity of Sin, Death, and the Devil (295). Redemption, in this context, is God’s work of setting things right by buying back humanity from the slave-auction of sin. The death of Jesus was not compulsory, demanding, or contrary to God’s own nature, rather it was an expression of God’s love.

The Wrath of God

The next biblical motif she reviews is judgment, what she labels “The Great Assize.” This moves our discussion into law-court metaphors. It would be remiss of me not to highlight her reference to Seinfeld, the greatest sitcom in American history, with her comment that we live in a “post-Seinfeld culture” that is steeped in anxiety but has no room for guilt.

The reality is that the grand biblical narrative is one where guilt/shame is a major element. We believe that Jesus will come again in glory to judge the living and the dead. This is a judgment that is both individual and corporate. According to Rutledge when the Bible is thinking about judgment it is thinking mostly “collectively,” “communally,” and ultimately “cosmologically” (312). The Powers will be judged. Nations will be judged. Structures will be judged in the end. All nations will stand before the Judge as Jesus taught in the parable of the sheep and goats.

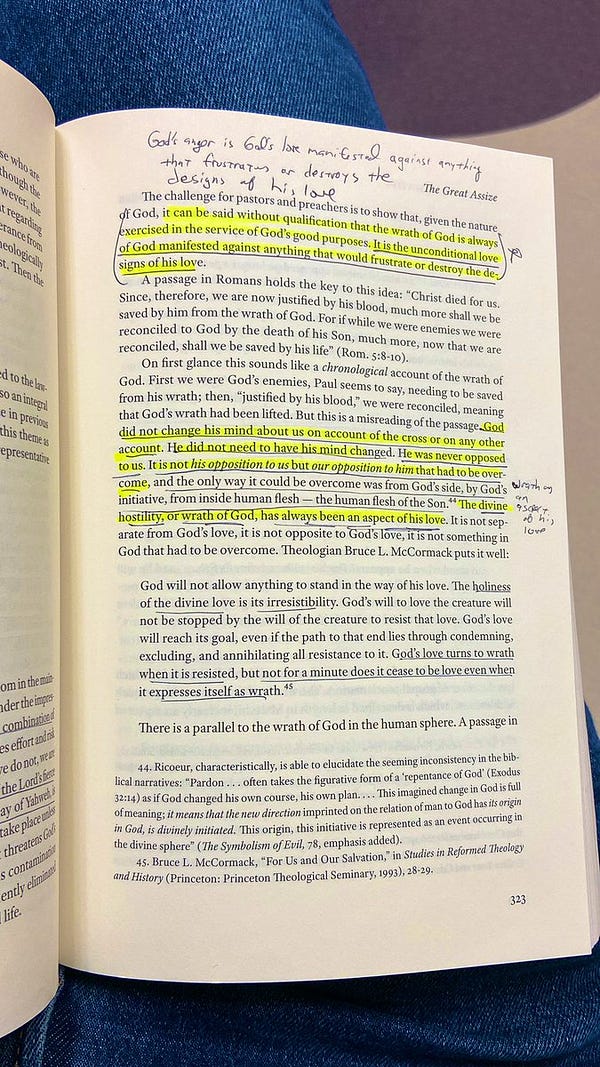

Jesus death rescues us from judgment as an expression of God’s love, “for us and for our salvation, God must be against all that would threaten or destroy that purpose” (317). The wrath of God, as I have argued, is best understood as a metaphor for the judgment of God. According to Rutledge, God’s wrath has always been God’s love in service of God’s purposes.

God’s wrath is connected to God’s righteousness, which is rightly interpreted by Rutledge as God’s justice. And contra to the neo-reformed crowd, God’s justice is not a matter of God’s need to punish sin, but God’s desires to right all that has gone wrong because of sin. Therefore God’s work of justification, or rectification, includes God’s work of reconciliation.

Wow! This post is getting long, so maybe I will bring things to a close right here.

Here is this week’s reading schedule:

Monday, March 20: Pages 358-374

Tuesday, March 21: Pages 375-390

Wednesday, March 22: Pages 390-406

Thursday, March 23: Pages 406-422

Friday, March 24: Pages 422-439

Saturday, March 25: Pages 439-455

Be sure to reserve Sundays as a rest day or a get-caught-up-on-reading day!

Also don’t forget to use the hashtag #ReadingRutledge if you are posting quote or thoughts on social media.

Fantastic treatment of the wrath of God...this book continues to deliver the goods...a great practice for Lent. This combined with reading/contemplating Brian Zahnd’s “The Unvarnished Jesus” have been a serious step forward in my Lenten journey. Also I appreciate the info/opinions/explanations in her footnotes...many writers and scholars are so sterile with their use of footnotes.